A Practical Comparison of Lithium-ion, LiFePO₄, NiMH, and Lead-acid Batteries

When people talk about batteries, the conversation often starts with numbers — energy density, cycle life, cost per watt-hour. In practice, however, battery selection is rarely that simple.

Different battery chemistries behave very differently once they are placed into real products, operating in real environments, with real users. What looks good on a datasheet does not always translate into long-term reliability or the lowest total cost of ownership.

In this article, we compare four commonly used rechargeable battery technologies — Lithium-ion (NCM/NCA), Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO₄), Nickel-Metal Hydride (NiMH), and Lead-acid — from a practical, application-driven perspective.

1. Overall Performance Comparison

| Item | Lithium-ion (NCM/NCA) | LiFePO₄ (LFP) | NiMH | Lead-acid |

| Energy Density | High | Medium | Low | Very low |

| Size / Weight | Smallest & lightest | Larger than NCM | Large | Largest & heaviest |

| Cycle Life | 800–1500 cycles | 2000–6000 cycles | 500–1000 cycles | 300–500 cycles |

| Safety | Medium (BMS-dependent) | High | High | Medium |

| Discharge Rate | High (3C–10C) | Medium–High (1C–5C) | Medium | Low |

| Cost per Wh | Medium–High | Medium | Relatively high | Lowest |

| Maintenance | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Environmental Impact | Good | Very good | Average | Poor (lead content) |

2. Understanding the Differences Beyond Specifications

At a high level, all rechargeable batteries work on the same principle: energy is stored and released through reversible chemical reactions. The difference lies in the materials used and how stable those reactions are under stress — heat, high current, deep discharge, or long-term cycling.

From an engineering standpoint, the most important questions are usually:

How long will the battery last in this application?

How tolerant is it to misuse or abnormal conditions?

How much protection and system-level control does it require?

What will it really cost over several years of operation?

With that in mind, let’s look at each chemistry in more detail.

Lithium-ion Batteries (NCM / NCA)

Lithium-ion batteries using NCM or NCA cathodes are widely known for one reason: they pack a lot of energy into a small space. This is why they dominate consumer electronics, drones, and many mobile robotic systems.

In typical designs, these cells operate at around 3.6–3.7 V nominal voltage, with energy densities reaching 180–260 Wh/kg, far higher than most other rechargeable batteries.

Where Lithium-ion Performs Well

If your product has strict size or weight limits, lithium-ion is often the first and sometimes the only realistic option. High discharge capability also makes it suitable for applications that demand short bursts of high power.

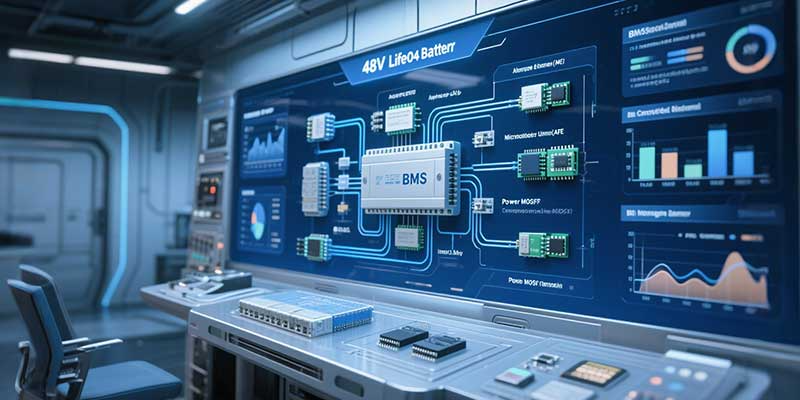

With a properly designed BMS, lithium-ion batteries can charge quickly, deliver stable performance, and achieve good overall efficiency.

Practical Limitations

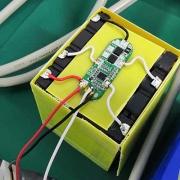

The trade-off is safety and complexity. NCM/NCA cells are less forgiving than other chemistries. Overcharging, overheating, or cell imbalance can quickly become a serious issue if protection is inadequate.

From experience, lithium-ion systems rely heavily on:

Accurate voltage and temperature monitoring

Cell balancing

Well-defined operating limits

This adds cost and design effort. In addition, cycle life is usually shorter than LiFePO₄, especially in high-load or high-temperature environments.

Typical Use Cases

Consumer electronics

Drones and UAVs

Compact robotic platforms

High-performance portable equipment

Lithium Iron Phosphate Batteries (LiFePO4)

LiFePO₄ batteries have earned their reputation mainly because of stability and safety, not because they win on headline energy density numbers.

With a nominal voltage of around 3.2 V per cell and energy density typically in the 120–160 Wh/kg range, they are physically larger than NCM-based lithium-ion batteries for the same capacity.

Why Many Engineers Prefer LiFePO₄

What LiFePO₄ offers in return is predictability. The chemistry is extremely stable, even under abusive conditions. Thermal runaway is far less likely, and the battery tends to fail gracefully rather than catastrophically.

Cycle life is another major advantage. In many real-world applications, 2000–6000 cycles is achievable, which makes LiFePO₄ particularly attractive for systems expected to run for many years.

Voltage output is also very stable during discharge, which simplifies system design in industrial and energy storage applications.

Known Trade-offs

The main downside is size and weight. If space is limited, LiFePO₄ may not be suitable. Low-temperature performance is also weaker compared to some other chemistries, and cold environments may require additional thermal considerations.

Typical Use Cases

Energy storage systems

Electric vehicles focused on safety and longevity

Industrial equipment

AGVs and forklifts

Telecom backup power

Nickel-Metal Hydride Batteries (NiMH)

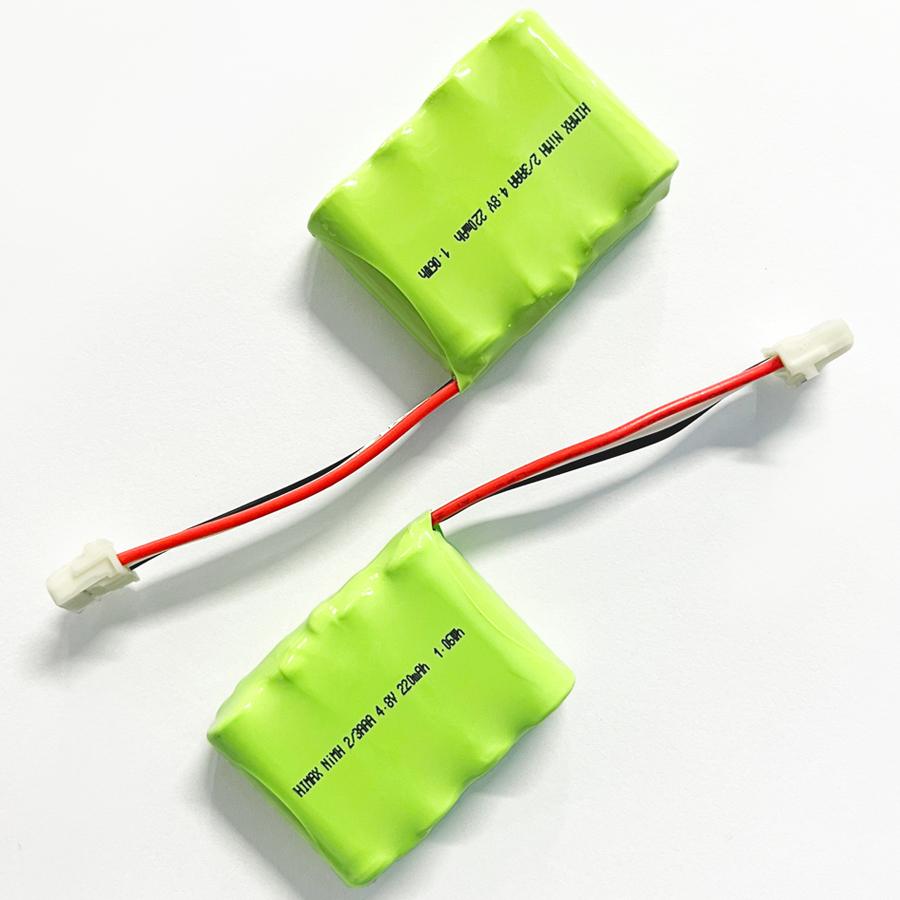

NiMH batteries sit somewhere between lithium-based batteries and lead-acid in terms of performance. They are not cutting-edge, but they are proven and reliable.

Operating at around 1.2 V per cell, NiMH batteries have relatively low energy density, typically 60–120 Wh/kg, which limits their use in modern compact designs.

Strengths in Real Applications

NiMH batteries are known for being robust and safe. They tolerate overcharging better than lithium-ion and perform reasonably well across a wide temperature range.

In applications where simplicity matters and advanced battery management is not desirable, NiMH can still be a practical choice.

Practical Drawbacks

Higher self-discharge means NiMH batteries are not ideal for long standby periods. In addition, their cost per watt-hour is often higher than lithium-based alternatives, which reduces their appeal in new designs.

Typical Use Cases

Medical devices

Measurement and instrumentation equipment

Older hybrid vehicles

Retrofit or replacement battery packs

Lead-acid Batteries

Lead-acid batteries are the most mature rechargeable battery technology still in use today. Despite their age, they remain common in applications where cost and simplicity outweigh performance considerations.

With energy density typically below 50 Wh/kg, lead-acid batteries are heavy and bulky, but they are also inexpensive and easy to manage.

Why Lead-acid Is Still Used

The technology is well understood, charging methods are simple, and the supply chain is fully established worldwide. For backup systems that are rarely cycled, lead-acid batteries can still make economic sense.

Limitations That Matter

Deep discharge significantly shortens lifespan, and cycle life is generally limited to 300–500 cycles. Environmental concerns related to lead handling and disposal are also becoming more restrictive in many regions.

Typical Use Cases

UPS systems

Engine starting batteries

Emergency power supplies

Cost-sensitive backup systems

Choosing the Right Battery in Practice

In real projects, battery selection is rarely about finding the “best” chemistry. It is about finding the most appropriate one.

When size and weight are critical, lithium-ion (NCM/NCA) is often the only viable option.

When safety, longevity, and predictable behavior matter most, LiFePO4 is usually preferred.

When simplicity and robustness are required, NiMH can still be a reasonable solution.

When upfront cost is the primary concern, lead-acid remains relevant.